The utopian sense of breaking with utopian fantasy in the video game Herald

Pim van den Berg

In video games the sailing ship has almost always been a symbol of exploration, possibility, autonomy, freedom, wealth, and power and hegemony in the positive sense – until now. The video game Herald (2017), developed by the small company Wispfire in Utrecht, is the first to explicitly tangle with colonialism. It is named after the 19th century merchant vessel on which the majority of the game takes place, and this ship comes to represent the flip side of colonial expansion and exploitation, not only within the game itself, but hopefully for video games as a whole.

Video games offer endless possibilities for lived, imagined spaces and worlds, yet most present utopian worlds that improve upon reality, (Schulzke, 2014, p. 2) and attempt to conserve that idyll, be they fantastical or rooted in history – regardless of the politics that exist within it, glossing over complications that would contradict these fantasies. Even most dystopias are appealing, removed from reality and its challenges by definition surmountable, meant to lure the player into spending as much time in them as possible, even if they fulfill their dystopian purpose on a strictly textual level.

By contrast, Herald acknowledges the lengths many games go to in order to preserve their fantasies of agency and utopia. Unlike for example the dour Papers, Please (2013), a game that achieves a similar effect by placing the players in the shoes of an overworked, conflicted border official of a fictional Eastern European country, the colorful Herald uses its deconstruction of utopian game space and player agency for reinvention, rather than cynicism. It looks towards the horizon.

Herald takes place in the 19th century, in an ‘alternative history’ where Western civilization has been united democratically into the so-called Protectorate, a super state spanning two continents. The titular merchant vessel ships the dye indigo from the Protectorate’s Eastern Asian colonies. Everything in the Protectorate is painted blue, derived from the indigo: its flags, its uniforms, the roofs of its houses. The Protectorate is literally draped in stolen wealth. It’s a visual simplification of colonial exploitation that not only gets the point clearly across, but it also adds to the wonderment of the Protectorate’s citizens of its orderly splendor. A beautifully monochrome city, or even an entire state, caters to a certain fantasy of order, and the power that precedes it. A few passengers and sailors on the Herald note as much.

On the other end, we have the lush colors of the beautiful Rani’s palace, where the main character Devan finds himself at the start of the game, narrating the events on the Herald as they are played. The Rani’s palace, with its pink hues, extravagant gardens, and gorgeous view of a sunset over the sea – a very distinct purple and yellow contrast that really speaks to the imagination – drives home the exotic beauty of the East. Herald doesn’t shy away from acknowledging that, yes, both East and West possess a fantastical majesty.

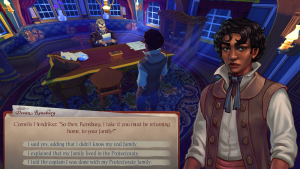

However, while showing or imagining the attractions of Western power and Eastern wonder, Herald simultaneously complicates, or even problematizes both, showing them for the illusions they are. The Protectorate’s colonial exploitation is made explicit, firstly by the treatment the main character receives because of his brown skin. Devan Rensburg is a young man born in India, but adopted and raised by white parents in the Protectorate. In search of his parentage and his homeland, he books passage on the Herald by working, first as a sailor, then as a steward.

On the ship Devan is confronted with the many forms of racism that exist within the democratic Protectorate. (One might’ve imagined that the early introduction of democracy also brought with it equal rights and liberties, but no.) A frustrated, colored junior officer’s insistence on his right to carry a firearm on board, against his white, Dutch captain’s orders, ends in possibly lethal tragedy. A Brazilian sous chef hides his illegitimate daughter with a slave woman as a stowaway, and is lashed as punishment. The most prominent passenger on board, a Protectorate diplomat, treats Devan with either haughty contempt, or condescending acknowledgement of Devan’s subservience, depending on the player’s competence as a steward, meaning: if the player complies to demeaning requests with elegance, and without question or complaint.

As Devan discovers, this diplomat is sent to India to resolve a strike by indigo plantation workers who feel they are being unfairly treated and exploited. Devan also learns that the Rani’s husband, the Raja, has presumably been assassinated in a Protectorate plot to either regain or increase control on its colony. As the game progresses, its imagined representations of East and West are irrevocably tainted by the violence inflicted upon it, resulting in a feeling of sorrow of innocence lost. (Fittingly, the symbol for the Protectorate is a rooster, a territorial bird plucking out the feathers of the peacock symbolizing the East. Ironically, the rooster is a bird of Eastern Asian origin.)

Oftentimes popular video games offer challenges to the player that are inherently and decisively assertive and meaningful, but Herald follows a more recent trend, where players are given a choice that is revealed to meaningless, thus removing the illusion of the power that the player usually has over its constructed game space. Herald applies this appropriately, by placing the player in the shoes of a protagonist of marginalized ethnicity, and in a profession of servitude. If the player had any fantasies of agency, freedom, and endless exploration, by the end of Herald’s first two chapters, they will very likely have evaporated. (Two more chapters to finish off the story are to be released sometime in the near future.)

While Herald seems to construct and immediately dismantle its own utopian fantasies of both East and West, it does offer new and fresh perspectives: not only on history and colonialism (as far as video games are concerned), but also on the medium of video games itself. So far, Herald is one of very few games that critiques and introduces ambivalence into its own fictional world as it appeals to both the player and its inhabitants, in order to progress into a more meaningful and constructive narrative – not just metaphorically, but also in reference to actual history. It pierces the seemingly comfortable illusions of so many other games, showing the courage necessary to confront its players with feelings of alienation, and at the same time, employs a wide variety of developers and voice actors to create a more pluralist experience. By doing so, it paves the way forward for video games themselves.

Works cited:

Herald: An Interactive Period Drama (2017). Wispfire, Utrecht. Windows.

Papers, Please (2013). 3909 LLC. Mac OS X.

Schulzke, M. (2014). ‘The critical power of virtual dystopias’. Games and Culture.

Pim van den Berg (1988) is a student of Comparative Literature and Postcolonial Theory, and also a freelance journalist. He has written about pop culture for Dutch magazines Vrij Nederland and De Groene Amsterdammer, as well as various video game websites, and writes his own blog for Dutch pop culture criticism, Zachte Krachten.